Hokkaido, Japan, Birding & Scenic Driving Road Trip in Autumn

Two Seasons in Hokkaido

In the summer of 2010, Hokkaido greeted us with the fragrance of lavender and the laughter of a tour group moving in unison. We followed the bright banners of our guide through Sapporo’s streets, along Otaru’s glass-lined canals, and across the patchwork hills of Furano. Cameras clicked like cicadas in the sun; ice cream melted faster than our attempts to capture the fleeting colors of the fields. At Daisetsuzan, clouds brushed the mountain peaks as if repainting them each hour. We were travelers then—eager, wide-eyed, content to be led.

Fourteen years passed, quietly but surely, like snow melting into spring. In the autumn of 2025. we returned—not as passengers this time, but as explorers behind the wheel of a six-seater Toyota Sienta. Hokkaido had changed, and so had we. The flowers had given way to gold and crimson leaves; the hum of tour buses had been replaced by the whisper of wind through open windows.

This time, our map was dotted with names of birds instead of attractions—marshlands and forests, lakes where the mist rose before sunrise. We drove where curiosity pointed: from the hush trails to the mirror stillness of lakes, where geese drifted like thoughts unspoken. Each stop was slower, each silence fuller.

In 2010, we came to see the beauty of Hokkaido. In 2025, we came to feel it, to listen, to wait, and to be part of it. Two journeys, two seasons—one island that keeps reminding us that wonder does not fade with time; it deepens with return.

Day 1: The First Forest Bird in Maruyama Park, Sapporo

From Odori Park, we descended into the hum of the subway—soft chatter, echoing footsteps, the scent of morning coffee. When the doors opened at Maruyama Koen, sunlight spilled into the station like a promise. We followed the laughter of school children heading toward the zoo, their small backpacks bouncing like bright birds themselves.

Halfway up, two women stood by the trail, binoculars steady, cameras poised. I asked, half curious, “何を見ていますか?”

They smiled. “Gojukara,” one said softly. The Eurasian Nuthatch.

And then I saw it — a tiny silhouette darting along the bark, moving headfirst down the trunk with a confidence that defied gravity. My camera clicked in bursts, heart pacing with every frame. When I showed them the photos, they nodded with gentle approval.

That was my first forest bird. Not just a sighting—but a beginning. It gave shape to the unseen world around me: the scale of the trees, the rhythm of stillness, the patience of looking long enough to truly see.

Later, I would learn their names—Willow Tit (Kokara), Coal Tit (Higara), Japanese Tit (Shijukara), Varied Tit (Yamagara), and the steady drummer, the Great Spotted Woodpecker. Each encounter is a brushstroke in a growing portrait of the northern forests.

By the pond, I met a gentleman named 星野英黒, standing quietly among reflections of mandarin ducks rippling in the autumn light. He pointed toward the trees and spoke in the language of birdwatchers—measured, reverent, wordless at times.

In that moment, Hokkaido felt infinite. Not because of its size, but because every leaf, every sound, every feather held a world waiting to be noticed.

Day 2: From Sapporo to Miyajima Numa Wetland (宫岛沼)

The morning light in Sapporo was gentle, filtered through a thin veil of cloud, as we set out toward Miyajima Numa Wetland, about 45 kilometers northeast. The highway soon gave way to open farmland—golden fields stretching toward the horizon, farmhouses sitting quietly under the wide sky.

The wetland appeared like a mirror to the heavens—broad, still, and alive with motion. Recognized under the Ramsar Convention, it felt sacred in its stillness, a sanctuary shaped by both nature and time. Here, among the reeds and shimmering shallows, thousands of Greater White-fronted Geese paused on their great journey southward.

From 10:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m., we stood at the water’s edge, lenses trained on wings and ripples. The air was filled with a wild chorus—geese calling across the water, the whistle of Northern Pintails, and the distant silhouette of Black-eared Kite gliding above the horizon. Every click of the camera felt like a heartbeat captured.

By noon, we turned the car eastward toward Furano, taking the mountain road that wound like a ribbon through forests. The journey took longer than we planned, but each bend revealed a new palette of autumn—amber larches, russet maples, and the fading green of summer’s edge.

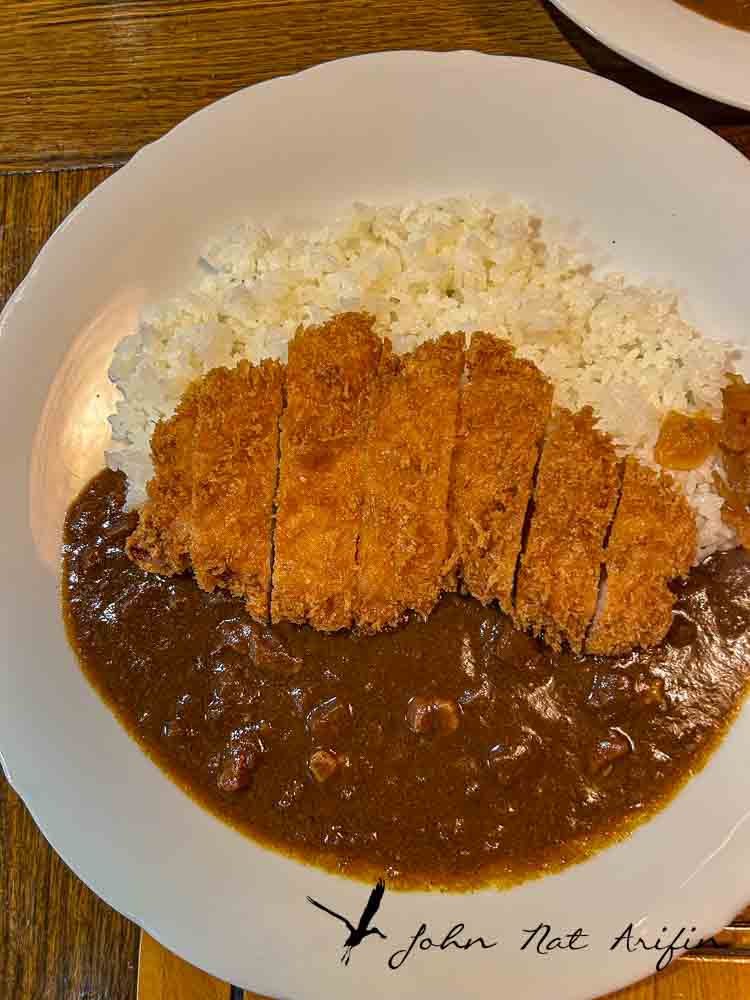

We reached Furano late in the afternoon, as twilight brushed the town in shades of violet and gold. Most restaurants were dark, doors closed for the day. Hunger turned our search into a small adventure of its own until we found Kumagera, its warm lights spilling onto the street. The pork cutlet curry rice was rich, comforting—food that tasted like gratitude.

We had hoped to see the Blue Pond in Biei, to catch the last light on its surreal turquoise water. But the sun had already slipped below the hills at five, leaving the landscape quiet and dim. So we drove onward to Asahikawa beneath a sky of stars, the roads empty except for the hum of our tires.

When we arrived, the town was asleep, the restaurants closed. We laughed softly at the silence and made our dinner from instant noodles and sandwiches bought at a late-night supermarket. Steam curled up from the cups as we ate in our hotel dining hall—a simple ending to a long, beautiful day.

Sometimes, travel is not just about what we see, but what we learn to let go of—the perfect plan, the perfect light. That night, even with tired eyes and simple food, Hokkaido felt perfect all the same.

Day 3: Daisetsuzan National Park: Asahidake, the Blue Pond, and Shirahege Waterfall

Daisetsuzan — the heart of Hokkaido — is where autumn unfurls its grandest tapestry. The locals call it Kamui Mintara, “the garden where the gods play,” and as we approached the mountains that morning, it felt exactly that — divine in its vastness, serene in its silence.

Sugatami Station Ropeway

There are two gateways into the park: Asahidake on the west and Sounkyo on the north. We chose Asahidake, drawn by the promise of steaming earth and open skies. At the visitor center, the chill in the air hinted that winter was already rehearsing its lines.

We took the ropeway to Sugatami Station gliding above slopes. The landscape opened like a painting in motion — birches trembling in the wind, clouds drifting low over the peaks. When we reached the top, Mount Asahidake (2,291 meters) stood before us — an ancient sentinel breathing white plumes from its crater. The smell of sulfur lingered in the crisp air, a reminder that the mountain was very much alive.

We paused for lunch along the trail — a simple meal against a grand backdrop. The bowl-shaped caldera rose like a fortress, framed by a sky so blue it seemed freshly painted.

Shirogane Blue Pond and nearby waterfall

From Asahidake, we descended and began the drive toward Blue Pond (Aoiike) and the nearby Shirahige waterfalls. The road wound through forest shadows until, just before sunset, we arrived. The light was perfect — golden rays dancing through the trees, turning the pond’s surface into shifting shades of sapphire and turquoise.

As twilight deepened into the blue hour, the colors grew quieter, more mysterious. And when we thought the day could not offer more, a moonrise began — a glowing disc lifting slowly over the mountains of Biei, washing the landscape in silver light.

It was one of those moments when time seemed to pause — the world perfectly still, except for the soft rustle of leaves and the sound of our own breathing.

Day 4: Daisetsuzan National Park: Sounkyo and Surrounding Valleys

If Asahidake was about power and grandeur, Sounkyo was about color and grace. They say it is the first place in Hokkaido to wear autumn’s full splendor — and when we arrived, the prophecy was true. The valley burned with gold and orange, each tree ablaze with life.

We took the Mount Kurodake ropeway, rising above a flaming carpet of leaves that shimmered like fire under the morning sun. The gondola floated silently through a sea of color, and from above, the mountains looked like a living quilt — stitched with red, amber, yellow and green.

From the upper station, we switched to a chair lift, open to the wind and the scent of pine. It carried us gently to 1,529 meters, where the view stretched endlessly — a horizon of layered peaks and rolling forests, each ridge fading softer into blue.

In the afternoon, we visited Ryusei and Ginga Falls — the “husband and wife” waterfalls — cascading side by side through stone and light. I sat by the riverbank for a long while, letting the sound of rushing water and rustling leaves fill the silence between thoughts.

Evening came quietly. We returned to the base of the cable car station, hunger leading us to a small diner where we ordered Jumbo Ramen. The steaming bowl was a simple reward — rich broth, tender noodles, warmth that settled deep into the bones after a day spent in the cold breath of the mountains

That night, the air in Sounkyo felt different — crisper, sharper, full of the quiet satisfaction that comes only from being completely present.

Day 5: Daisetsuzan National Park: Mikuni Pass

Morning mist still clung to the valley when we left Sounkyo, the air cool and thin, carrying the faint scent of cedar. Our first stop was Obako Gorge, where the cliffs rose steep and solemn, their volcanic faces streaked with age. The Ishikari River wound quietly below, its waters flashing silver in the sun. We lingered there for a while—just long enough to feel the pulse of the landscape—before continuing our ascent toward the highlands.

The road to Mikuni Pass curled upward like a ribbon through the mountains. Highway 273, they say, climbs to the highest point of any road in Hokkaido, near Mount Mikuni (1,541 meters). Each turn revealed a new burst of color—hills glowing in magma-red and golden-orange, birches trembling in the wind, larches catching the sunlight like burning torches.

When we reached the Mikuni Bridge, the world opened wide before us. Below lay the vast sprawl of Daisetsuzan National Park, a sea of peaks and valleys drenched in autumn fire. The air was cold and perfectly clear. We stood there for a long time, the wind tugging at our sleeves, as if urging us to remember this view—not just with the camera, but with the heart.

Descending from the pass, the colors softened into gentler tones. We stopped for lunch by Lake Nukabira, a tranquil expanse born from the dam built in 1955. The water mirrored the crimson of nearby maples, the occasional ripple distorting the reflection like brushstrokes on glass.

From there, the road stretched long into the evening. The drive carried us through miles of open landscape—forests giving way to farmland, daylight fading into dusk. The headlights carved narrow tunnels of light through the dark.

It was well past midnight when we reached Kojohama. The town slept under a pale moon, and the streets were empty except for the whisper of the wind. We checked into our hotel quietly, too tired to speak, yet filled with the quiet satisfaction of a day well spent—a day that had shown us both the grandeur and solitude of Hokkaido’s mountains.

Sometimes, the most memorable journeys end not with applause, but with silence—the kind that lingers long after the road has ended.

Day 6 & 7: Noboribetsu and the Salmon Run

Morning broke quietly over Kojohama, the sea stretching out in silver and gray. After days in the mountains, the change in scenery felt almost like stepping into another world. Gone were the flaming forests of Sounkyo; here, the landscape was carved from volcanic rock, shaped by the restless sea. Steam rose faintly from fissures in the earth, and the air smelled of salt and sulfur — a reminder that Hokkaido’s fire runs deep beneath its calm surface.

We set out toward the town of Shiraoi near Kojohama, where rivers thread through valleys on their way to the Pacific. This time of year, the waters come alive — not just with the current, but with movement from another world: the salmon run.

Somewhere along a quiet road, we stopped in a small village, unsure of the right turn. With my limited Japanese, I asked a man standing in front of his house, “サーモン、どこですか?” — “Where can we see the salmon?” He smiled — that kind of simple, unhurried kindness that travelers never forget — and without hesitation, gestured for us to wait. Moments later, he pulled up in his Jeep and motioned for us to follow.

We trailed him through winding lanes until the road opened beside a shallow river. There, the salmon were swimming downstream — their bodies flashing silver and crimson as they fought the current, driven by instinct stronger than exhaustion. The sound of the river filled the air — a ceaseless murmur of water and life.

We stood in quiet awe. Around us, leaves drifted from the trees, floating briefly before joining the current — another small migration in the endless rhythm of nature.

As the man waved goodbye and drove off, I felt a quiet gratitude — not just for his kindness, but for the way travel sometimes unfolds like this: one simple question leading to something deeply beautiful.

From mountain to sea, from color to stone, Hokkaido kept revealing new faces of the same wild spirit — resilient, ancient, and endlessly generous.

Day 8 & 9: Lake Toya and the Fruit Orchard

Morning mist floated above Lake Toya, soft as breath against the still surface of the water. The caldera lake shimmered under the pale sun, its volcanic origins hidden beneath a calm too deep to guess. Across the lake, the peaks stood solemn.

We left the lakeside and took Highway 393 toward Otaru, the road winding through hills and valleys like a ribbon drawn by memory. A few hairpin turns clung tightly to the cliffs, and each curve revealed a different face of the mountains — one moment shadowed and dark, the next glowing with light. From the scenic viewpoints, the snow-covered volcanic peaks gleamed against the horizon, their whiteness pure and absolute. It felt as though autumn and winter were meeting halfway, shaking hands in the cold air.

Midway through the drive, we stopped by a fruit orchard at Sobetsu, rows of trees heavy with late-season apples and prunes. The air was sweet with the scent of ripened fruit and fallen leaves. A farmer, wrapped in a worn jacket and kindness, offered us freshly picked apples. Their crispness was almost startling — sharp, sweet, alive with the taste of the land.

From there, the road descended gently toward Otaru, the sea once again filling the distance with its calm expanse. The journey had come full circle — from the lavender plains of summer remembered, to the mountains of fire and color, and now to the quiet harvest of autumn.

As the day faded, I thought of all the landscapes that had passed through our windows — and how, in return, they had quietly passed through us. We thank God for the blessing, the excellent weather we had, the people we met in Hokkaido and good company to enjoy His creations.

I believe you meant Kojohama (not Kojimama you mentioned), a town after Shiraoi and before Noboribetsu.

It is a very long drive from Lake Nukabira to Kojohama; a shorter drive and more accomodation options should be putting a night at Obihiro and a more leisure drive next day to Noboribetsu.

I had been to almost the same route but in reverse direction including Miyajima Numa Marshland in July 2025. Thanks.

Leon, you are right about Kojohama. Thank you. We had booked the hotel in Kojohama , therefore we had to reach the destination. We did stop in Obihiro for dinner.

How was the wetland in July, any birds?

John, good write-up and photos…Hokkaido is my top favourite to-go prefecture for sakura, lavender, autumn leaves, and winter.

Phyllis, thanks for your comment. We hope to go back again soon for spring .